Recent Articles

Three Ways Your Organisation Can Support...

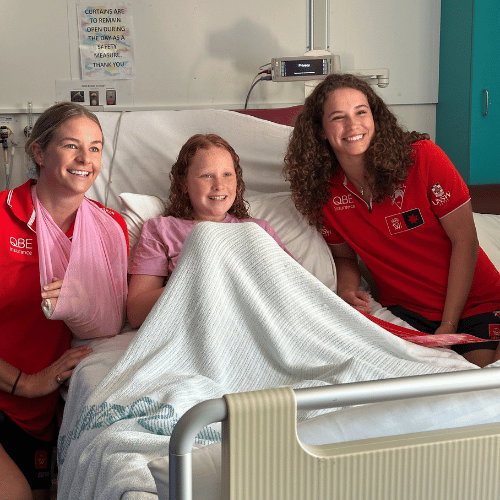

Help give more kids like Abigail the gif...

The best gift you can give this Christma...

Support Sydney Children’s Hospitals Fo...

Teddy rings the bell: a brave little fig...

Lara Hausegger joins as an ambassador

Remy’s road to recovery

Changing the future of craniofacial care

Turn Your Halloween Decorations into a F...

SCHF takes the stage at SxSW Sydney: The...

Out of This World: Astronauts Land at Sy...